Boldly going

Nicholas Dobson explains why he is upbeat about what the general power of competence offers local authorities

Nicholas Dobson explains why he is upbeat about what the general power of competence offers local authorities

Many local government lawyers remain spooked by LAML (1). For when, back in June 2009, the Court of Appeal found the former well-being power in section 2 of the Local Government Act 2000 did not in fact allow authorities to set up and fund a mutual insurance company, many council lawyers seemed to lose both vires confidence and creative mojo.

Whether or not this was justified (and personally I think it wasn’t, if well-being were to have been used properly) the confidence slump remained. Much potential council creativity therefore lay grounded.

However, a solution arrived on 17 February 2012 when (following the Bideford Town Council prayers case (2)) Eric Pickles activated a new general power of competence in Part 1 of the Localism Act by making the requisite statutory order (3). This new power is now familiar territory for council lawyers. But a spirit of pessimism (or at best muted optimism) still seems to prevail.

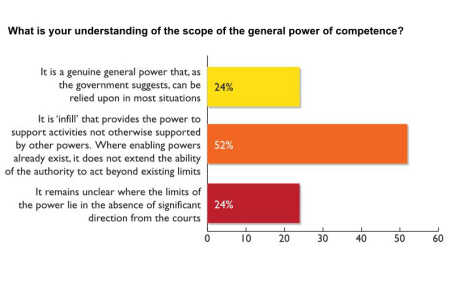

For in the Local Government Lawyer/Freeth Cartright LLP Localism Act survey conducted for this supplement, 49% of respondents said that the competence power made no difference to the local authority appetite for risk, compared with another slightly more optimistic 45% who discerned a ‘slight positive difference’. Only 6% were at that stage bullish enough to judge that the power had made a ‘significant positive difference’. True, while there were some more positive narrative responses (including one noting “a general cultural change and a ‘can-do’ approach”) the prevailing tone was rather lacklustre.

Reasons to be cheerful

Personally I am much more upbeat about this power. Why? Because it bends over backwards to show how extensive and flexible it is. After conferring power on local authorities to do anything that individuals of full capacity generally may do, the measure makes clear that councils can shake off the rusty fetters of custom. For the power applies to things ‘even though they are in nature, extent or otherwise’ unlike anything the authority may otherwise do or unlike anything that other public bodies may do.

The measure also extends to the UK or elsewhere and (unlike well-being) gives power to do it for or otherwise for the benefit of the authority, its area or its residents. In LAML, of course, the Court of Appeal found that the well-being power did not enable the authority to act for its own economic benefit. In that regime there had to be a nexus between the proposed action and the relevant element of well-being (economic, social or environmental). The competence power is entirely free from such constraints and is a strong and substantial primary power.

True, existing statutory restrictions overlapping use of the power will continue to apply. However, this seems to me not unreasonable for public bodies funded by the public purse. And any such restrictions should usually be fairly obvious for most seasoned local authority lawyers. I doubt whether (as some have suggested) a detailed trawl of the entire statute book will be necessary before any action is taken.

|

| The competence power does enable authorities to be bold, creative and innovative. It seeks to demonstrate this acrobatically on its face. Nevertheless, given that they are spending taxpayers’ money, authorities should take action prudently, looking carefully before they leap – as any sensible individual would do before spending their hard-earned money. |

Nevertheless, it will, of course, be wise to check to see whether any existing statute covers the area of the proposed action and if so what limitations, if any, it has. With modern electronic law libraries this should usually not be too onerous.

It is an irony that this power arrived just when stringent fiscal austerity was kicking in. But although straitened finance undoubtedly removes some lustre, there still remain creative community leadership possibilities – for example, facilitating local voluntary or charitable effort to support vulnerable elderly people beyond the limits of statutory resource. For local people do see their council as the natural community leader.

Be confident

The Department for Communities and Local Government pointed out in May 2011: “It is important that the general power should not only increase local authority powers, but increase the confidence of local authority officers and members in the scope of those powers.”

And, for those seeking guidance or a possible pre-authorisation mechanism for proposed action (reservations which continue to be aired): “The general power of competence has been designed to give councils the confidence to act, using the power as their primary tool, without needing to refer back to central government. How they use the power is up to them….” Nevertheless, public bodies should clearly not play fast and loose with public money. Successful businesses will not spend substantial resources without getting a sound business case approved at senior level and by the board if necessary. Local authorities should be no different.

So, bearing in mind their constitutional base, councils should ensure that the proposed action is reasonable in all the circumstances, is taken in light of all material considerations and is a proper and prudent use of the authority’s financial and other resources. It is also useful to ensure that all the legal bases for the decisions to be taken are specified in the decision report.

In addition consideration should be given to:

• whether (and if so why) the proposed project is considered to be the most effective means of meeting the proposed objectives;

• the financial, human and other resources (including skill bases and management time) likely to be needed and how these can be utilised most efficiently, effectively and economically;

• likely ongoing cost, affordability and potential financial returns (if any);

• the specific benefits likely to be accrued for whom and over what period;

• any risks involved and how these can be mitigated;

• the degree of alignment and compliance with statutory duties (including equalities and human rights considerations) and the authority’s strategic objectives;

• the time period for the project and whether the authority’s involvement can gradually wind down to enable the community to assume broader responsibilities where appropriate;

• whether the project can be more effectively and economically rolled out (perhaps with others) over a wider regional footprint;

• whether any applicable public law duties (for example fiduciary duty and fairness) have been properly met.

Conclusion

The competence power does enable authorities to be bold, creative and innovative. It seeks to demonstrate this acrobatically on its face. Nevertheless, given that they are spending taxpayers’ money, authorities should take action prudently, looking carefully before they leap – as any sensible individual would do before spending their hard-earned money.

If local authorities do so and can demon-strate sound public benefit reasons for their actions, they should have nothing to fear where necessary from Star-Treking for the benefit of their communities. In other words, boldly going where no authorities have gone before.

Dr Nicholas Dobson is a consultant with Freeth Cartwright LLP specialising in local and public law. He is also Communications Officer for Lawyers in Local Government. He can be contacted on 0845 017 7620 or by email at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

(1) Brent LBC v Risk Management Partners Limited and London Authorities Mutual Limited and Harrow London Borough Council as interested parties [2009] EWCA Civ 490.

(2) See R (National Secular Society) v Bideford Town Council [2012] EWHC 175) where on 10 February 2012 Mr Justice Ouseley found that, although lawfully based council prayers would not be inherently discriminatory and would similarly not contravene Convention rights, in the circumstances, section 111 of the Local Government Act 1972 (which enables authorities to do anything calculated to facilitate, incidental or conducive to the conduct of their functions) did not empower prayers as part of formal council business.

(3) The Localism Act 2011 (Commencement No. 3) Order 2012 (S.I. 2012 No. 411).