Reasons to be cheerful

Lawyers in local government are happier than most other professionals, according to this year’s survey. Derek Bedlow looks into why they are reporting record levels of satisfaction with their work and outlines areas where working conditions can still be improved.

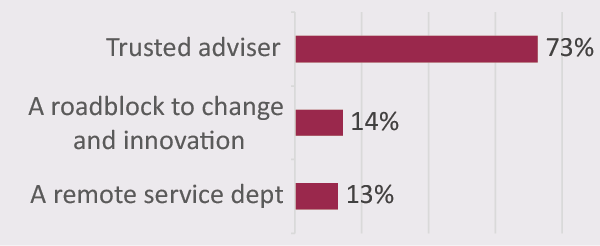

First, some good news. 85% of local government lawyers would recommend a career in local government law (FIG 1) and 83% would recommend their own department as a place to work.

| Figure 1: Would you recommend local government law as a career? |

|

The figures for local authority lawyers represent a significant improvement on the scores they gave when the Legal Department of the Future survey was last conducted in 2015. Then, the average ratings for recommending your career and recommending your employer were 70% and 72% respectively, still reasonably healthy but some way off this year’s figures.

The proportion of local government lawyers who would recommend their career choice compares very favourably with other professions. According to the 2019 version of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development’s (CIPD) Employee Outlook, just 69% of all workers were satisfied with their jobs.

|

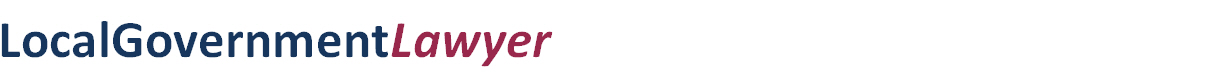

Shared Services: Try it – you might like it! In this year’s survey, shared services legal departments continue to be a turn-off for a significant proportion of local government lawyers, 35% of whom say that they would be less likely to apply for a vacancy in a shared legal service, compared with just 10% who would be more likely to apply. The remainder said that it would make no difference to their decision. Although shared legal services have become a more established form of in-house legal provision since the last time this survey was conducted in 2015 the proportion of lawyers that would be deterred from applying for a job with them has actually gone up by 6% since then. However, there is a stark difference in these – and other – figures between those who currently work in a shared legal service and those who don’t. For example, those who already work in a shared services environment (approximately one-quarter of respondents) are actually more likely to be attracted by a job in a shared service than repelled by it. Twenty-five per cent of this cohort said that they would be more likely to apply for a job in a shared service compared with 22% who said they would be less likely to. By contrast, only 4% of those not currently working in a shared legal team would be more likely to apply to one, while 40% would be put off. We also asked respondents to rate how working in a shared services would affect some of the key aspects of their working lives (FIG 5). Those already working in shared services were much more likely to be positive about the experience than those in single authority teams, especially in relation to both the variety and quality of work, job security and client relationships. In fact, of those working in shared services, only one aspect – manageability of workload – gets more negative than positive ratings. Amongst other lawyers, six do. Figure 5: What effect would (or does) being employed in a shared services department have on the following aspects of your working life and career?

Some other differences emerge between the two groups. Those in shared services were slightly less likely to describe their department as a trusted adviser (68% compared to 72%) and more likely to say that their clients considered them to be a remote service department (17% v 10%). However, fewer people in shared services (10%) thought that they were a roadblock to change and innovation than those in single authority teams (15%). Those in shared services are also more likely to want promotion than other lawyers and more likely to want to be specialists (64% v 58%) rather than generalists. “I enjoy being in a specialist team in a shared legal service - it is preferable to my previous experience in a small district,” said one. Perhaps most importantly, there was no discernible difference in the answers between shared and non-shared service employees when asked if they would recommend their department as a place to work. So, it seems, to a large extent the apparent unpopularity of shared services amongst lawyers is more a matter of perception than reality. |

Local government lawyers also express higher levels of job satisfaction than teachers (69%, according to the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey), doctors (83%, Medscape.com UK Doctors’ Salary and Satisfaction Report 2019), management accountants (76% of AAT members) while 59% of social workers are planning to leave their jobs in the next 18 months, according to research by Bath Spa University (UK Social Workers: Working Conditions and Wellbeing) published in August last year.

They also do well compared to lawyers in other parts of the profession, according to research conducted last year by recruitment site CV-Library, which found that 50% of lawyers were unhappy with their current jobs with the biggest gripes being “feeling undervalued”(61%), “not being in the role they want” (60%), “being bored” (41%) and “poor company culture” (40%).

The benefits of being busy

So why are local government lawyers apparently noticeably happier than they were four years ago? One answer is that many are less concerned about redundancy than they were.

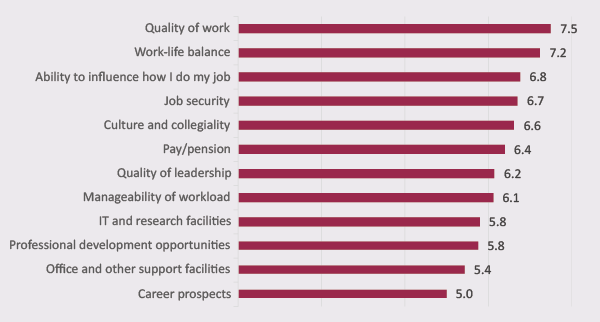

Looking at the ratings for satisfaction with specific aspects of their work (FIG 2), the respondents this year scored, on average, their happiness with work 0.5 higher (out of 10) than they did in 2015. However, satisfaction with job security jumped from an average rating of 5.4 in 2015 to 6.7 this year, the biggest rise of any of the 12 categories in the question.

Figure 2: On a scale of 1-10 (with 10 being most satisfied), how satisfied are you with the following aspects of your employment?

|

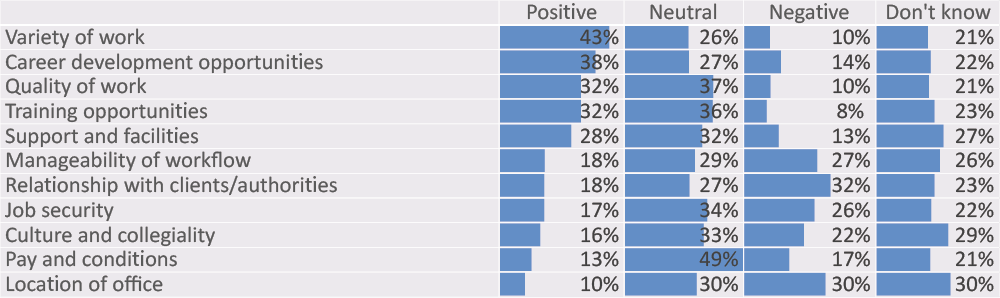

A question of trust There has also been a marked improvement in how local government lawyers feel they are perceived by their authorities (FIG 3). Almost three-in-four (73%) think that their team is considered, in general, to be a “trusted adviser” by their authorities, a 5% rise on 2015. By contrast, 13% say that their department is a “remote” service department while 14% think that it is perceived as a “roadblock to change and innovation”. Figure 3: How do you think the legal department is generally regarded by your authority (or authorities)?

“I think the department is currently considered as all three at times,” said one respondent. “I am not confident that it is truly considered by all to be a trusted adviser although it is moving more and more towards this. [In the past], the team was very much considered a roadblock due to the speed of service and the lack of desire to be facilitative. This has changed. Now, we are seen as a roadblock only when there are governance and/or process issues and we do not simply ‘rubber-stamp’ everything. “Some teams do consider us to be a remote service department but this is definitely improving due to the hard work of the team (following new staff appointments) to market the team and network internally.” In the open comments for this question, quite a number of people added the caveat that the view would vary depending on which client department or director was asked and that the perception was as much to do with the attitude and approach of the client as with the culture of the legal team. “It will depend on the client department and the point in any project when legal advice is requested,” said one in-house lawyer. “If legal comes to the table late we are usually seen as obstructive but if we are in at the beginning of the project we can have a very positive relationship.” While there were also one or two comments about how shifting to a shared service and/or ABS had damaged client relationships, the proportion of those respondents currently working in a shared legal department who felt that they were “trusted advisers” – 68% – was not dramatically lower than those in single authority teams at 72%. |

The next biggest risers are career prospects, up by 0.7 (albeit from a low base), the ‘ability to influence how I do my job’ (up from 6.2 to 6.8), work-life balance (up from 6.7 to 7.2) and quality of work up (up 0.4 to 7.5). The only key aspect of lawyers’ working lives that has not shown much improvement is pay/pension, up just 0.1 to 6.4.

However, four key categories remain below a ‘satisfactory’ score of 6 out of 10 – IT and research facilities, professional development opportunities, office and support facilities and, last of all, career prospects.

The survey also asked lawyers what they thought the best and worst aspects of working for local government were. Although this was asked as an open question rather than multiple choice, by grouping similar comments together we have created the statistical charts on these pages (FIG 2 and FIG 3).

When it comes to the best aspects of working in local government, two factors stand out – flexibility/work-life balance and the quality and variety of work provided, which were mentioned by a little over (54%) and a little under (44%) one-half of respondents respectively.

“The work/life balance is generally better than any other legal sector,” one lawyer told the survey. “The quality of work, particularly for junior lawyers, is far beyond what any other sector can offer.”

Strong secondary reasons for working in local government are the public service aspect of the role and the culture and collegiality of their teams, mentioned by approximately one-fifth of lawyers who took part in the survey.

“I like knowing that I am working for the public,” said one respondent. “We work on a huge range of projects that serve many different people, and it is great to know that I have a small part in it. I used to work in the private sector and the change from working for profit only, to working for the good of everyone, is one of the best parts of my work.”

By contrast, the list of pet hates about working in local government is more diverse, although the lack of funding experienced by local government in recent years is a common theme.

Given the pay freeze over the past decade, pay is unsurprisingly an issue (mentioned by 26%), but the biggest single complaint relates to a lack of resources and support to enable lawyers to do their jobs to the best of their ability.

“Support staff are now extremely thin on the ground which makes life very stressful and work inefficient and everything that hasn’t already actually fallen apart feels as though it is just about to,” said one lawyer.

Other factors to gain significant mentions include a lack of career prospects and poor leadership, although a number of comments suggested that there was relatively little that legal department management could do to alleviate some of the problems that they face.

Up or out?

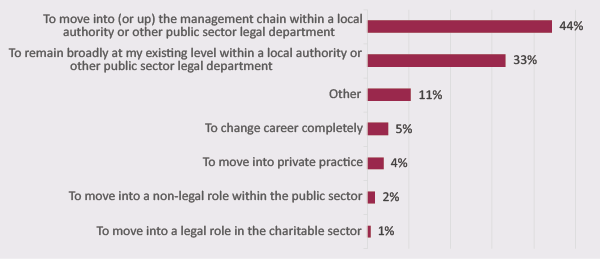

Despite the gripes and ongoing resource issues in local government, it is clear that morale in general has improved. One effect of this, compared to the last Legal Department of the Future survey in 2015, is that a greater proportion of local government lawyers want to stay in local government and a greater proportion of them want to move up the career ladder too. In 2015, when asked what their main career ambition was, 32% of local government lawyers said that their future careers lay outside local government.

This time around (FIG 4), this proportion has dropped to 23% and of those that intend to remain in the sector, the majority say that they would like to move into (or further up) the management ranks rather than remain in their present pay grades.

Figure 4: What would you describe as your main career ambition?

Meeting these career demands will not be any easier for legal department management. The growth of shared services has reduced the number of more senior roles available as has the relegation of the monitoring officer role down the corporate hierarchy at many councils. As a result, while improved from earlier surveys, local government lawyers’ satisfaction with their career prospects remain pretty low at just 5 out of 10. The phrase “dead man’s shoes” crops up frequently in the open-ended comments.

Meeting lawyers’ career ambitions is perhaps a different management headache to those faced in the past few years, but one that is probably preferable to managing a demotivated workforce.

Derek Bedlow is the publisher of Local Government Lawyer. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

This article appeared in the Legal Department of the Future report, published in November 2019. To read or download the full report, please click on the following link: http://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/legal-dept-of-the-future