Focus on site notices

- Details

Sarah Reid and Constanze Bell examine the thorny issues around publicity for planning applications in the coronavirus outbreak.

During our recent virtual seminar, “Planning for Flexibility” in the coronavirus crisis, hosted by Kings Chambers and Women in Planning, there was a recurrent theme in the questions raised by delegates: What to do about site notices and publicising applications during lockdown?

That concern is understandable.

On the one hand, there is a common desire amongst all those involved in the development industry to keep the system moving. That is clearly critical for the economy, and also to ensure that the pipeline of much needed development is maintained.

What are the requirements of the legislation, and how are publicity requirements to be fulfilled during lockdown?

And what about communities? There is also an understandable concern that communities are not disenfranchised from a process that will continue to shape their environment long after this crisis is over.

This article addresses some common concerns as to the legal obligations that apply in respect of publicity requirements and site notices, and also seeks to look at some of the wider questions and concerns that might arise in these unprecedented times.

(1) Is this a type of application that needs a site notice?

One concern that is arising frequently is how site notices are to be posted in accordance with legal requirements during lockdown.

The first question to ask, however, is whether a site notice is actually required.

Article 15 of the DMPO [1] sets out the circumstances where a site notice will be required. However, close inspection of that Article reveals that a site notice is in fact only required for a relatively limited number of types of applications. These are applications:

- EIA development accompanied by an ES (Article 15 (1A));

- Affecting a right of way (Article 15 (2));

- That do not accord with the development plan (Article 15 (2);

- For technical details consent (where not major development or development that falls under Article 15 (2) (above)).

But for all other types of applications, both for Major Development and Minor Development, there is no express requirement to publicise the application by way of site notice (See Articles 15 (4) and 15 (5)). In those cases, there is a choice as to how the notification / publicity requirements will be fulfilled. Therefore, in those cases, serving notice on adjoining owners and occupiers will suffice to meet the publicity requirements of the Order (in addition to publication of the notice in a local newspaper in the case of applications for Major Development).

Serving notice on adjoining owners and occupiers is self-evidently something that can be done by post, and should not create issues in respect of the Coronavirus restrictions.

What if there is a SCI that requires something different?

The Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 requires that an LPA must prepare a statement of community involvement (‘SCI’) [2]. The SCI should set out how the LPA will involve people who have an interest in development matters in their area. An SCI review must be completed every five years from the date of adoption [3]. In R. (on the application of Majed) v Camden LBC [2009] EWCA Civ 1029, the Court of Appeal considered a case where the council's SCI, which set out the minimum standards for planning application notifications by letter, site notice and advertisement, had not been adhered to in several respects. The standards went beyond statutory requirements. The Court of Appeal held that the SCI was a “paradigm example” of legitimate expectation. Local Planning Authorities would be therefore well advised to check whether any additional publicity obligations (over and above those imposed by statute) are imposed by their SCI.

(2) Is there a tension between the obligation to display a site notice and the coronavirus restrictions on movement?

The authors of this article do not think that there is.

The Coronavirus Regulations [4] provide that:

“6 (1) During the emergency period, no person may leave the place where they are living without reasonable excuse.

(2) For the purposes of paragraph (1), a reasonable excuse includes the need –

(h) to fulfil a legal obligation”.

Where a Local Planning Authority posts a site notice, it is fulfilling a legal obligation to publicise applications for planning permission in accordance with the requirements of the DMPO (or SCI, where there is an obligation to do so). Fulfilling a legal obligation is expressly an exception to the restrictions on movement in the Coronavirus Regulations, and the authors’ view is that there would be no breach of restrictions on movement in these circumstances.

However, if the Authority remains concerned about this, then in circumstances where neighbour notification is an alternative contemplated by the Order, the Authority can fulfil its legal obligations in respect of publicising the application by notifying adjoining owners and occupiers directly as an alternative to posting a site notice (see above).

(3) Who should be posting the site notice? Can Local Planning Authorities ask Applicants to do this?

It is important to remember that the duty to publicise the Planning Application expressly falls on the Local Planning Authority.

This is because Article 15 (1) DMPO provides that,

“An application for planning permission must be publicised by the local planning authority to which the application is made in the manner prescribed by this article.”

It is therefore the authors’ opinion that the responsibility for publicising the application lies firmly at the door of the LPA, and that they have a duty to ensure that the publication requirements of the Order are met.

(4) What form should the site notice take?

Notwithstanding the above, we understand that some LPAs have been requesting Applicants to post their own site notices. For the reasons set out above, we are not convinced that this is what is required by the Order.

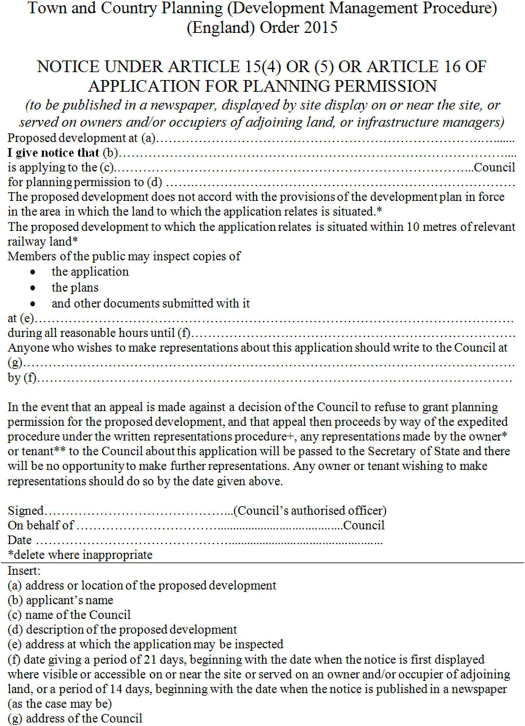

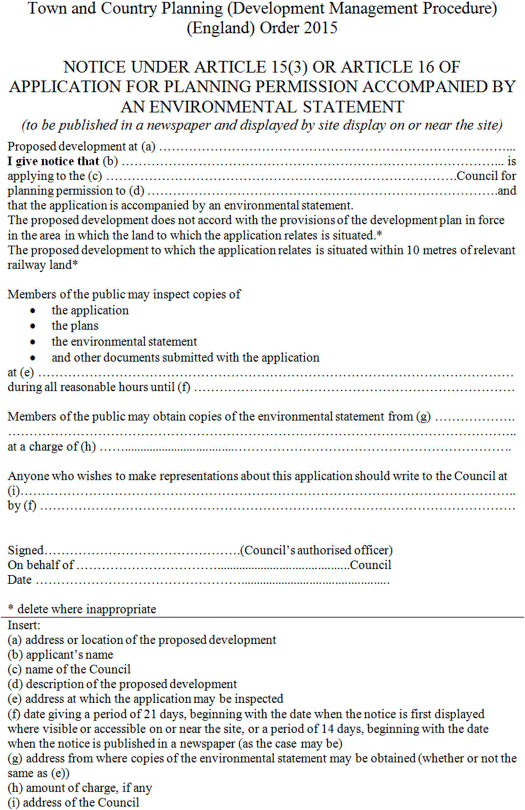

However, irrespective of the approach taken, in all cases, the “requisite notice” that is required by the Order means a

“notice in the appropriate form set out in Schedule 3 or in a form substantially to the same effect.”

The Forms contained in Schedule 3 are set out at the end of our article for ease of reference.

Even if that form is not used, care should be taken to ensure that all of the information contained therein is included in the site notice to ensure that the form is, at least, a form that is “substantially to the same effect” as that within Schedule 3, within the meaning of the Order.

(5) But what about Officers’ safety?

It is fully understood that this is a critical consideration for all in these unprecedented times.

As a matter of practice, in normal times, it might be the LPA’s usual practice to display a site notice in all cases. However, during the outbreak, the LPA might wish to consider whether it can fulfil the legal requirements in the DMPO by way of direct neighbour notification instead (see above). As set out, notifying adjoining neighbours and occupiers by post, where this is permitted by the DMPO as an alternative to displaying a site notice, is unlikely to raise any significant issues in the outbreak.

Where a site notice is required by the DMPO, however, the LPA will want to consider carefully its own arrangements for ensuring Officers’ safety. Practical solutions might include driving to the location where the site visit will be posted, checking that other people are not in the vicinity before leaving the car and posting the notice, declining to enter into conversations with members of the public, and maintaining social distancing measures (although the above should not be seen as a comprehensive list, and in all cases the responsibility will be with the Local Planning Authority to take all necessary and appropriate steps to protect the safety of Officers).

(5) But what about Community engagement?

Planning approvals have the ability to shape our communities long after the current crisis is over. Many Local Planning Authorities are understandably concerned to ensure, not only that the appropriate boxes are ticked having regard to the requirements of the DMPO, but that publicity is genuinely adequate to bring applications to the attention of residents.

The difficulties that might arise are obvious. If individuals are self-isolating, they might not see site notices. If notices are only sent to adjoining owners and occupiers and site notices are not posted, then others in the wider community might not become aware of the application. This might be a particular concern in respect of applications for Major Development, where the wider community might typically be expected to be interested in the application under consideration. Publication in a local newspaper might not have its normal reach, because people are only leaving the house for essentials.

It is important to note that the obligations in the DMPO are a “floor” and not a “ceiling”. That is, the obligation is for the LPA to comply with the minimum requirements of the DMPO. If it does so, it will have complied with the requirements of the legislation, and the authors consider that, as a matter of law, it can then proceed to determine the application in the ordinary way.

However, there is nothing to stop LPAs, or indeed Applicants as part of their community engagement, in going further in order to attempt to bring applications to the attention of the wider community. This is, of course, a matter of discretion for the LPA as oppose to a legal requirement. However, if the LPA is concerned about community engagement in respect of a particular scheme in their locality, they might want to think outside the box in this respect.

For example, in addition to posting site notices and notifying adjoining neighbours and occupiers, additional and wider mailshots might be contemplated. Additional user friendly information might be posted on the LPA’s website. The potential of well used community websites might also be considered, and telephone conversations with Parish Councillors, Ward Councillors and Community organisations might alert those groups to the application so that those groups can publicise the application on their own websites and through their own channels.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the authors of this article see no insurmountable barriers to the determination of applications on the basis of the publicity requirements of the legislation in during the coronavirus outbreak. For most types of applications, alternatives exist to publicising the application by way of site notice, but in any case, the authors do not consider that the restrictions on movement in the Coronavirus Regulations restrict LPA Officers from posting site notices in fulfilment of their legal obligations.

A greater challenge is likely to be a practical one, namely, continued community engagement in these unprecedented times. LPAs might wish to “think outside the box” in order to ensure that not only are the minimum requirements fulfilled so that the system can be kept moving, but that communities continue to be engaged in a process that has the potential to shape their community long after this crisis is over.

Sara Reid and Constanze Bell are barristers at Kings Chambers, and Committee Members for Women in Planning North West and Yorkshire.

[1] The Town and Country Planning (Development Management) Procedure (England) Order

[2] at section 18

[3] By virtue of regulation 10A of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 (as amended)

[4] Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020/350

Sponsored articles

Unlocking legal talent

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

Commercial Lawyer

Legal Director - Government and Public Sector

Locums

Poll