The EIP: 10 Days of the 10 Goals - Goal 10: Access to nature

- Details

Margherita Cornaglia examines the final goal of the Government's Enviromental Improvement Plan 2025.

A whistlestop tour of Goal 10

Goal 10 promises inclusive access to nature, sets out to reduce both physical and intangible barriers, and envisages better connections between public bodies, landowners and communities. Its centrepiece is a commitment to ensure everyone has access to green or blue spaces within a fifteen-minute walk from home. The EIP ties Goal 10’s commitments to health outcomes, noting that regular nature contact improves mental and physical health, reduces inactivity, and eases demand on health services. To move from aspiration to practice, the plan outlines nine National River Walks, three new national forests, a refreshed Green Flag award scheme, expanded Access for All infrastructure on National Trails, and a new accreditation model (to be launched by April 2026) for urban greening focused on areas with high environmental and social need. It also proposes to repeal the 2031 cut-off for recording historic rights of way, to explore access to unregulated waterways, and to support local authorities to embed Natural England’s Green Infrastructure Framework in local plans and strategies.

Goal 10 is explicit about inequality. It recognises that people living in more deprived areas, many ethnic minority communities, younger people and disabled people too often lack accessible, high-quality nature near home. The plan proposes pathways to close these gaps. Finally, Goal 10 couples access with stewardship: it foregrounds responsible access and the protection of fragile habitats, linking public use to nature recovery rather than treating them as in tension.

This is a coherent package, but two design questions remain. First, which parts are enforceable, by whom, and when? Secondly, what happens if they are not fulfilled, either nationally or locally? The plan notes that Defra will soon consult on the Access to Nature Green Paper (which the EIP promises will be published during this Parliament). That consultation and any subsequent policy decisions may be pivotal, acting as the bridge between promises and action, at a moment when civil society is demonstrating that judicially enforceable frameworks, transparency and credible delivery plans are decisive for environmental law.

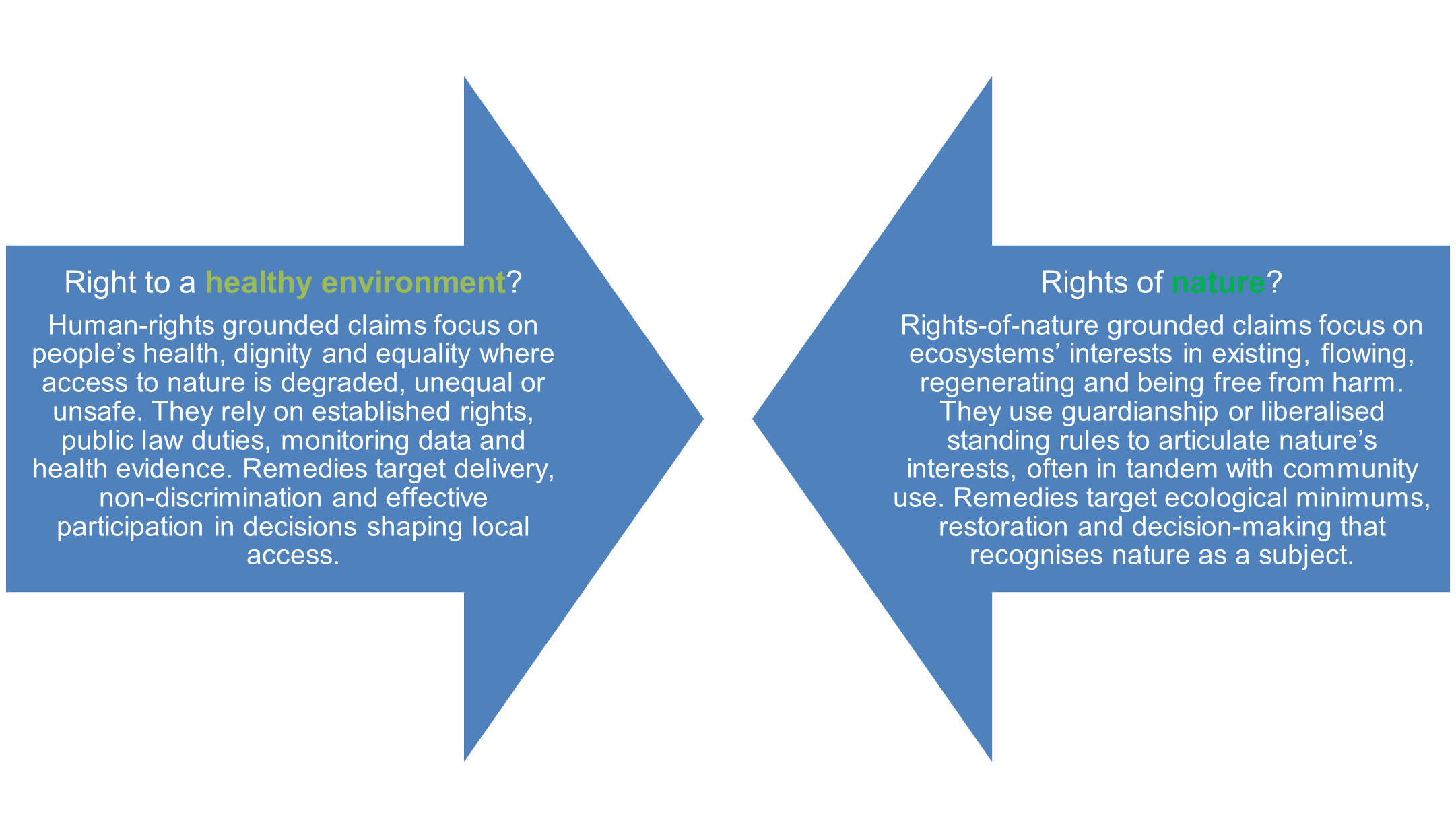

Goal 10 and the Right to a Healthy Environment

The United Nations General Assembly recognised the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in 2022. Shortly thereafter, the International Court of Justice recognised the right to a healthy environment in its advisory opinion on climate change. While the resolution and advisory opinion are not self-executing in the UK, they form part of a growing international consensus that health, dignity and environmental integrity are inseparable. The European Court of Human Rights has long considered environmental harms through the lens of established rights, particularly private and family life, property, and sometimes life itself.[1] The direction of travel is clear: there is a growing recognition that a healthy environment is a precondition to the enjoyment of human rights.

We are yet to see a claim brought domestically seeking to tie access to nature to the right to a healthy environment. As Goal 10 highlights, however, access to nature is precondition to good physical and mental health. Furthermore, by creating metrics for access and green infrastructure, and by promising evaluation frameworks to track progress, Goal 10 accepts that access to nature is measurable and consequential. Should significant delivery gaps persist geographically, or across protected characteristics, arguments that a failure to realise reasonable access is unlawful and/or constitutes an unjustified interference with private and family life may become stronger. Specific policies or processes promised by Goal 10, such as the Access to Nature Green Paper consultation, could provide the legal foothold for claims seeking to ensure ambition in implementation.

Similarly, failures to deliver clear promises (such fifteen-minute access to nature routes at local level) may be vulnerable to judicial review. Where any such shortfall systematically burdens protected groups, the public sector equality duty adds weight. Where the failure is severe and sustained, and degraded access systematically burdens particular groups (such as communities in deprived urban areas), reaching the requisite threshold of harm, this may give rise to arguable violations of Article 8 ECHR. In this respect, the European Court of Human Rights’ consistent message in climate and environmental litigation before it, i.e., that states must supply credible plans that can actually be delivered, may facilitate these claims: it will not be enough to rely on vague or high-risk enablers, or on unquantified good intentions.

Well-considered arguments in any such claims may strengthen the link in law between a healthy environment and traditional human rights. They may also move us closer to a less anthropocentric understanding of human rights…

Goal 10 and The Rights of Nature

Whenever I think of access to nature and associated debates, I think back to Stone’s Should Trees Have Standing? Stone argued that we already treat corporations as legal persons, we already appoint guardians for infants and people lacking capacity, and that our law therefore already recognises fictions when they serve real interests. His basic claim is that nature’s interests can be represented through guardianship models without metaphysical gymnastics.

European law has historically hesitated in moving so far beyond our traditional, anthropocentric systems of law. However, very recently Spain conferred legal personality on the Mar Menor, and the Spanish Constitutional Court upheld the move’s constitutionality in November 2024. The Mar Menor Act of 2022 accepts the legitimacy of non-anthropocentric approaches when traditional tools fail to halt ecological degradation. Mar Menor’s early case-law also speaks to cross-border recognition, with the Swiss authorities treating the lagoon as a legal person for the limited purpose of accessing environmental information.

The UK is experimenting at the local level too. Lewes District Council recognised rights for the River Ouse in 2024, committing to respect the river’s right to flow, to be free from pollution, and to be restored. This is not national legislation, and its enforceability remains untested, but it is a culturally significant choice by a public authority, aligned with the EIP’s emphasis on river walks, blue space and the health benefits of water. Declarations of this nature alter expectations and invite administrative practice to take a nature-centred turn. Promised public processes, such as consultation over the Access to Nature Green Paper discussed in Goal 10, may provide openings for the public to ask authorities to consider local guardianship models, with clear standing and duties, for defined ecosystems that anchor major access corridors.

Does Goal 10 move us any closer to guardianship models for specific green and blue ecosystems? The EIP stops short of that step. Even so, the weight it gives to nature, both for the ecosystem services on which we depend and as something of intrinsic worth, may signal the start of a shift in how governmental, administrative and legal processes conceive of the natural world. That shift would bring the UK closer to established traditions elsewhere, particularly in parts of Latin America, where nature is treated not as an external object but as embedded within social and legal systems, and therefore deserving of stronger protection through bespoke legal procedures.

Two legal futures for nature?

Conclusion

Goal 10 affirms that access to nature is not a luxury but a public good with demonstrable health and equity benefits. The EIP’s commitments are a meaningful step in that direction, yet our natural ecosystems are becoming more degraded, less healthy and less accessible at vertiginous speed. Translating Goal 10’s promises into clear duties and remedies will therefore be essential. If the plan’s monitoring and governance architecture matures as envisaged, Goal 10 can sharpen accountability and open more space for civil society to press for a stronger defence of nature. As government increasingly embeds nature’s role in protecting health and sustaining thriving communities, the legal conversation will evolve too: the connections between environmental quality and human rights will come into sharper focus, and with them the appetite, and the opportunity, to advance domestic jurisprudence on the right to a healthy environment and on the rights of nature.

Margherita Cornaglia is a barrister at Landmark Chambers.

[1] On this point, I’d recommend Kobylarz et al.’s book, Human Rights and the Planet, which looks at how the European Court of Human Rights is addressing the human rights impacts of the interlocking environmental and climate crises.

Must read

Sponsored articles

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

Unlocking legal talent

26-02-2026

05-03-2026 5:00 pm

01-07-2026 11:00 am