Dealing with easement claims

- Details

A rigorous and confident strategy from the outset is key to providing certainty with easement claims. David Nuttall presents a procedural roadmap for these cases.

Easement disputes are a staple of real property practice. Some can be of very high value, particularly where the existence of an easement has an impact on a development. Many, however, arise out of neighbour disputes. Despite having a more modest value, these claims are no less important to the parties involved and indeed can be no less complex. As with all neighbour disputes, costs have a tendency to spiral.

It is therefore important to have a firm grip on how an easement claim is going to progress. This can be difficult because often these claims can be very urgent.

Easement disputes between neighbours often focus on what in the Midlands we call jitties. Everyone else just calls them alleyways or paths. What follows is a typical example. I have broken down the procedure into rigorously practical steps. I am not going to go into the law on prescriptive easements in this note.

Most of these procedural steps are judgment calls. There is seldom a right or wrong answer, and even less common can you find the answer in a book. The steer will come from your own experience, practices of your local court and confidence in dealing with procedural challenges.

The case study

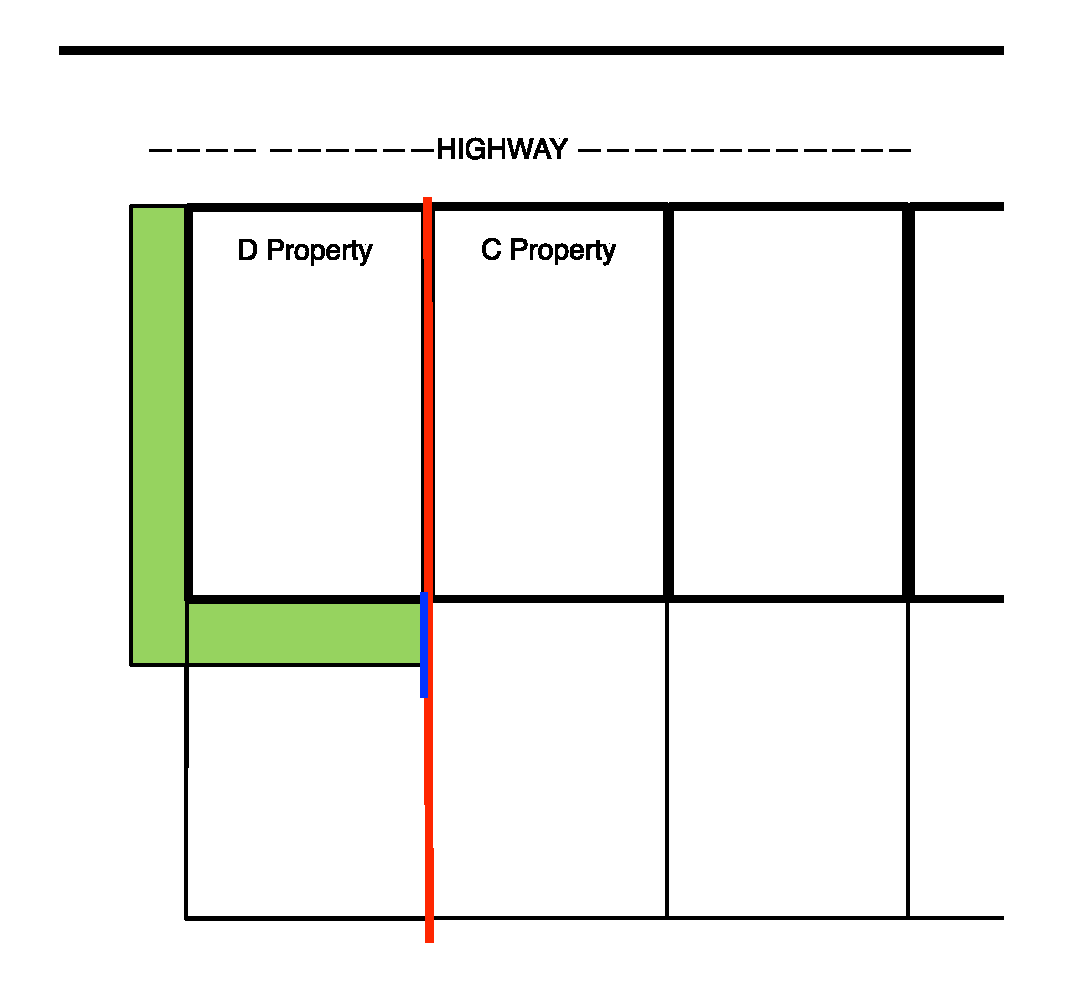

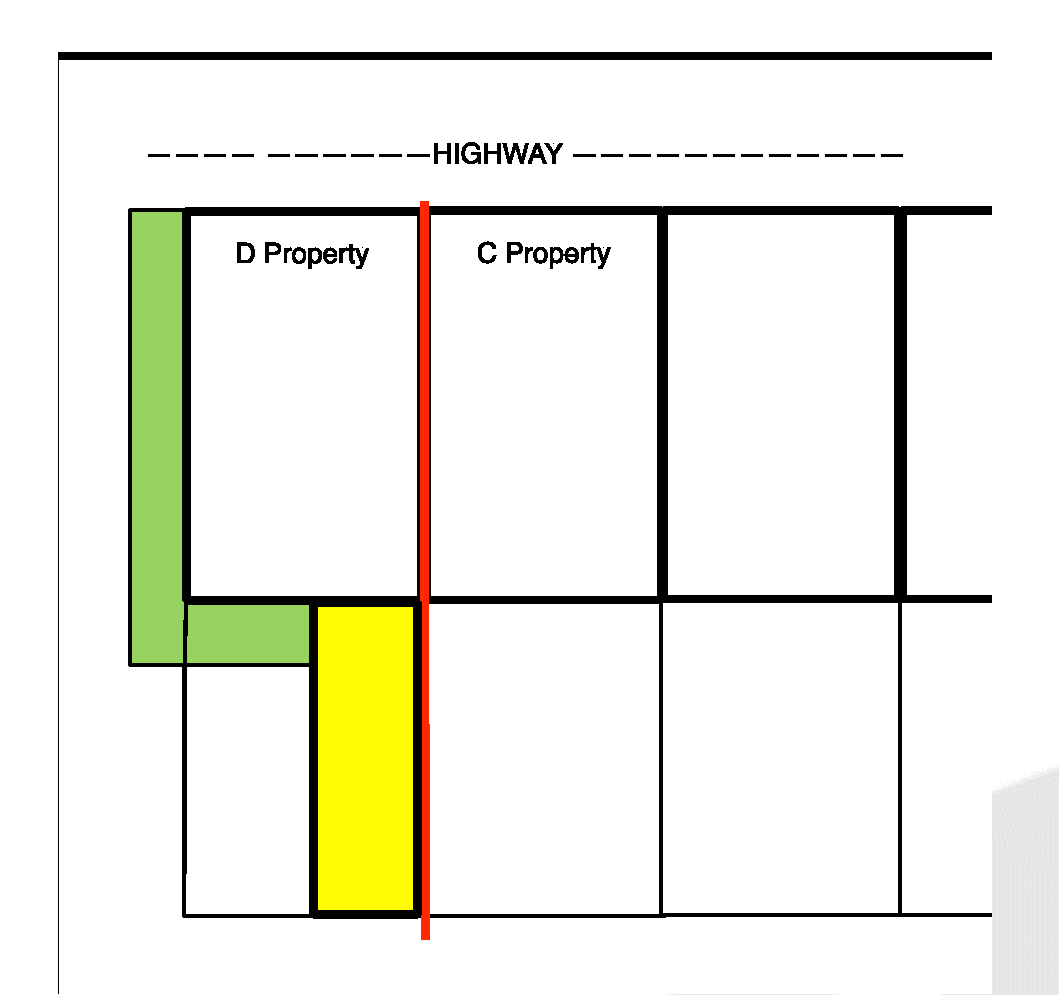

Below is a plan showing a fairly common situation:

- The Client owns C Property;

- C Property is in a terrace of houses;

- The north-facing front of C Property abuts the highway;

- To the west of C Property is D Property, which is at the end of the terrace

- Neither property has a front garden, both have rear gardens which are separated by a fence. There is a gate in the fence, coloured blue, near to the south sides of the houses;

- There is a path down the side of D Property leading from the highway to its rear garden. This is coloured green on the Plan [“the Pathway”];

- For a considerable period of time, the Client and her predecessors in title have used the Pathway to access the rear garden of C Property. This includes using it to take large deliveries to the rear garden and to put out the bins.

One day, the owner of D Property (Mr D) applied for planning permission to build an extension to the rear of D Property. The Client objected but permission was granted nonetheless.

The planned extension will abut the boundary and block the gate. There is no plan to replace the gate, and as such the Client will entirely lose the ability to access her rear garden via the Pathway. The planned extension, coloured yellow, is as follows:

Just recently, building materials have started to be delivered to Mr D. Mr D has stated that he intends to commence works within the next week, but it appears that preparatory works have already started.

The Client has asked Mr D to suspend the works for 28 days whilst she takes legal advice, but Mr D refused, saying that the deeds never gave the Client a right to use the Pathway anyway. He also denies that the Client’s predecessors regularly used the Pathway. The Client has asked you to send an urgent letter, which has been ignored. The time has come to urgently escalate matters.

Procedural roadmap

The Client’s objectives are usually quite straightforward:

- She wants to be entirely vindicated;

- She wants that to happen straight away; and

- She wants that to cost nothing.

Now, achieving that blessed triumvirate is probably not too realistic. However, our job is to get as close as possible with the tools available. Which processes to use requires some thought and an analysis of what we have to hand. It is therefore important to put together a procedural road map, which requires consideration of the following questions:

- Do we use Part 7 or Part 8?

- Do we issue an Interim Injunction Application?

- What is the sequence of events?

Part 7 or part 8?

Some key rules of the CPR:

- 8.1(2)(a) – Criteria for Part 8 to be used;

- 8.1(3) – Court’s power to transfer a Part 8 claim over to Part 7 procedure;

- 8.2(b) – That a Part 8 Claim Form must include a question to be answered or a remedy to be granted;

- 8.4 – Consequence of Defendant not responding to Part 8 Claim;

- 8.5(1) – Requirement to file written evidence with a Part 8 Claim Form.

This is a question which can cause a degree of anxiety, as it is sometimes not entirely clear cut as to which process to use.

Both processes have benefits. For Part 7:

- There is certainty of process;

- Both sides’ cases are fully set out from the outset;

- Default judgment is available;

- There is more likely to be an order for standard disclosure;

- Costs do not need to be front-loaded – disclosure (unless the Disclosure Pilot applies) and preparation of evidence come much later;

- Track allocation can sometimes help focus minds.

For Part 8:

- A hearing will be listed reasonably quickly, at which you may be able to secure some kind of remedy;

- That first hearing can be expedited if necessary;

- There is far more flexibility over directions, which means the litigation could be resolved quicker;

- There is no presumption that there will be a CCMC or cost budgets;

- You will have an idea of the height of the Defendant’s evidence from the outset.

Just as a refresher, Part 8 is intended for claims where there is unlikely to be much dispute of fact, and where ideally the evidence can be dealt with on paper. That said, practically speaking, judges may case manage on the basis that there will be some oral evidence at trial without a wholesale transfer over to the Part 7 procedure.

The safer route is to use Part 7 if there is doubt. In ING Bank NV v Ros Roca SA [2012] 1W. L.R. 472 the parties were criticised by the Court of Appeal for not applying to transfer over to the Part 7 procedure, with service of proper pleadings, when it became apparent that there was a factual dispute.

In Cathay Pacific v Lufthansa [2019] EWHC 484 (Ch) the Court urged litigants who were considering using Part 8 to take the following pre-issue steps:

(a) The proposed Defendant ought to be notified that the use of CPR Part 8 is being contemplated.

(b) A brief explanation ought to be provided as why CPR Part 8 is considered to more appropriate than under CPR Part 7 in the particular circumstances of the case.

(c) A draft of the precise issue or question which the Claimant is proposing to ask the Court to decide ought to be supplied to the Defendant for comment.

(d) Any agreed facts relevant to the issue or question ought to be identified. The obligation to take these steps can be derived from the broader duties imposed on parties in CPR 1.3 ('Duty of Parties to help the court further the overriding objective') and Paragraph 3 (a), (b) and (e) of the Practice Direction on Pre-Action Conduct and Protocols.

If the case is too urgent to go through any meaningful pre-action process, it would seem advisable to at least be prepared to address points (b) and (c) to the judge at the first hearing, and thereafter to seek to agree facts with the Defendant.

In this Case Study, I would consider the following:

- What is the factual dispute? Is there any doubt that the Client can establish 20 years continuous use? Bear in mind that there is an evidential presumption that, if the Client can prove 20 years continuous use, such use was as of right. If there is no doubt that this can be proved, and the question is simply one of actionable interference, Part 8 may well be viable;

- If, on the other hand, there is a serious question mark over establishing 20 years use, or if you know Mr D will be positively asserting that the use was not as of right, Part 7 is likely to be more appropriate;

- If the Client knows she can establish 20 years use as of right, but requires time to obtain statements from her predecessors in title, she might be best simply using Part 7 so that there is less time pressure on getting the statements;

- There may be other related circumstances where Part 8 is appropriate, such as:

- Interpretation of whether an express easement is wide enough to cover a certain use;

- Consideration of whether a certain activity by the servient owner amounts to actionable interference;

- Determination of whether there has been 20 years use as of right, where, say, it is agreed that certain signage had been erected by the purported servient owner which may defeat the easement.

On the facts set out in this Case Study, Part 7 is the way to go. There may be a dispute as to 20 years continuous use, and we probably have to assume that there are going to be wider disputed facts in establishing the prescriptive easement. There is also a degree of urgency, and we might not be able to gather evidence from our predecessors in title quickly enough to establish a Part 8 claim.

Interim injunction?

Whether we use the Part 7 or Part 8 process, we need to consider whether to issue an interim injunction application at the same time (or earlier).

That said, just because we can apply for interim injunctions does not necessarily mean that we should. As with deciding on the correct procedure, it helps to carry out a sensible and thorough analysis.

It is important to bear in mind what kind of evidence is required to justify an interim injunction, and to ensure this is ready when the application is issued. Taking these from Fellowes & Son v Fisher [1976] 1 QB 122, the Applicant needs to demonstrate:

- Some good explanation as to why damages will not be an adequate remedy (which should not be too difficult where the servient owner is looking to permanently block the route of an easement);

- A logical assertion as to why the cross-undertaking of damages will be sufficient for the Defendant;

- Some robust evidence on why the balance of convenience weighs in favour of the Client; and

- (Crucially, but often missed) Some clear financial evidence demonstrating the Client’s ability to meet any cross-undertaking of damages.

We can assume in a case like this that there is a serious issue to be tried, and as such, there does not need to be a focus on the underlying merits of the claim.

The following considerations may weigh against making an interim injunction application:

- Whether the application is actually necessary – has the Defendant committed an actionable interference or is it just anticipated? If anticipatory, can the Client make out the test for a quia timet injunction, which is:

- That there is a strong probability that the Defendant will do harm to the Client; and

- That that harm, once it is caused, cannot be reversed or restrained by an immediate interim injunction, or compensated by damages (Elliott v Islington LBC [2012] EWCA Civ 56)

- Whether the necessary evidence for an interim injunction can be obtained;

- Whether the Client is actually prepared to give the cross-undertaking, with its effects having been fully explained;

- Whether the Client is prepared to potentially add more delay to the resolution of the main proceedings, particularly if the interim injunction application is adjourned off;

- Whether the Client can afford to fund the interim injunction application, bearing in mind that, even if successful, the Court often orders costs in the case.

That said, there are undeniable advantages to making the interim injunction application in appropriate cases:

- A very swift hearing, generally in front of a circuit judge. Even if adjourned, a Defendant may be prepared to offer an undertaking pending the adjourned hearing;

- The interim injunction hearing can also sensibly be used as a directions hearing on the main claim. This can save an awful lot of time, particularly if the case is clearly suitable for fast track. Ideally, the Court can cut out the requirements for DQs and simply direct through to trial, potentially saving months of time;

- The Defendant’s response to the Application may well tell you a lot about their approach to the main claim;

- If an interim injunction is put in place, and so any works are suspended, it will lessen the chances that the Client will need to ask for a mandatory injunction at trial, which is generally more difficult to obtain than prohibitory;

- If an interim injunction is obtained, and the Defendant can live with it, it may lead to a swifter settlement.

In this Case Study, I would advise issuing an application for an interim injunction, subject to the points at Para 26 above. It would allow the Client to achieve some of the advantages of a Part 8 claim and hopefully expedite matters to a final resolution.

Timings

Some key rules:

- 25.2(2) – An interim injunction should only be issued before the main claim where the matter is urgent or it is otherwise in the interests of justice;

- 25.3 – Interim injunctions can be made without notice only if there is a good reason, and supported by evidence stating reasons why notice has not been given;

- PD A to 25, Para 4.4 – steps to be taken if an interim injunction is issued prior to issuing a claim, usually requiring Applicant’s undertaking to do so;

- 7.5 – Four months for service of a Claim Form

The Court has power to issue an interim injunction application before the main claim, but there is quite a high threshold for doing so. I would struggle to identify any common scenarios in easement claims which would justify doing this.

The more usual sequence would be as follows:

- Issue the claim and interim injunction application at the same time;

- If the matter is particularly urgent take along a certificate of urgency and ask to either see a judge there and then, or urge the Court to list an on-notice hearing as soon as possible;

- Arrange for service on the Defendant of:

- The Claim Form;

- Interim injunction application;

- Any order the Court has made listing the injunction application hearing the injunction application.

- Arrange for attendance at the interim injunction application. Assuming that this is less than 14 days post-issue, directions can be sought as to service of the Particulars of Claim if these are yet to be served. Otherwise, ensure that Particulars of Claim are served no more than 14 days after service of the Claim Form (and no later than the last day for serving the Claim Form, if for some reason that is earlier!)

Procedural Roadmap – conclusions

Bringing all of the above points together, the process I would therefore adopt in the Case Study is as follows:

- Assuming building work has not yet commenced, but will shortly, send one final letter inviting Mr D to provide an undertaking not to carry out any works within 48 hours;

- During those 48 hours, see the Client and focus on obtaining the evidence necessary for an interim injunction application. Ask her to bring bank statements. Ask her to consider the practical effects of losing the Pathway;

- Prior to the 48 hours expiring, draft:

- The Part 7 Claim Form;

- N244 seeking an interim injunction;

- N16 draft order;

- The Client’s witness statement in support of the injunction application;

- A certificate of urgency, if necessary;

- After the deadline, go to Court, issue the Claim Form and interim injunction application (there may only be one fee). Ask the Court to list the interim injunction application before a CJ within 7 days, and seek a notice of hearing to that effect.

- If the matter needs to be heard in less than 3 days, prepare and issue a further N244 seeking that the Court shortens the time for service required by CPR 23.7(a)(b) pursuant to CPR 3.1(2)(a), and ensure that that application is heard by a DJ on the day and an order drawn up to that effect;

- Serve, ideally personally, everything on the Defendant;

- Attend the hearing and either secure an interim injunction or brief directions to a contested hearing;

- Prepare Particulars of Claim, if this has not yet occurred, and serve them no more than 14 days after serving the Claim Form (or at such other time as the Court may have directed, which may well be shorter).

If the above steps are followed, at the end of a very hectic few days, the matter will hopefully be set up to resolve the Client’s issues as efficiently as possible.

Whilst the eye-watering costs of a neighbour dispute might not be avoided, at least some further certainty might be achieved by formulating a rigorous and confident strategy from the outset.

David Nuttall is a barrister at St Ives Chambers. He can be reached

Sponsored articles

Unlocking legal talent

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

Legal Director - Government and Public Sector

Commercial Lawyer

Locums

Poll