The EIP: 10 Days of the 10 Goals - Goal 1: Restored Nature

- Details

Natasha Jackson begins a series of articles on the Government’s EIP (Environmental Improvement Plan) goals, looking at restoring nature.

Image credit: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (GOV UK)

The EIP 2025 opens with a rousing Ode to Nature worthy of Wordsworth. We are reminded that “We all need nature. It provides the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat”. That “Nature is the foundation of our wellbeing, our economy and our communities” and that, in the face of risks including declining soil health, water scarcity and biodiversity loss, “it is imperative we come together, as a nation, to protect and restore nature”.

And thus, Goal 1 opens with the rallying cry that: “We want people to hear birdsong in their neighbourhoods and see wildlife in our landscapes. We want everyone, regardless of where they live, to be able to experience nature.”

And so, with a hand to our hearts and tears in our eyes, we get into the details…

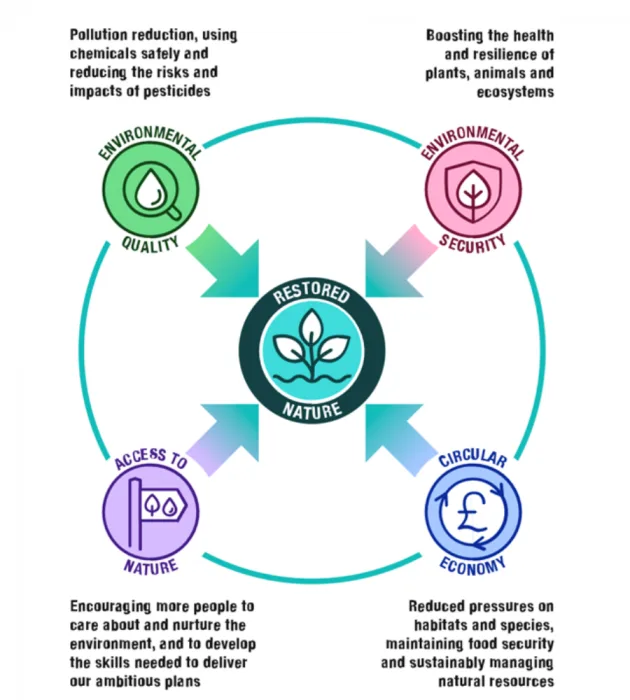

Goal 1 is the EIP’s overarching goal, which sets the foundational ambition on which the following chapters and goals rest. EIP 2025 itself acknowledges that restoring nature will only succeed if the pressures on habitats are also addressed via cleaner air, cleaner water, safer chemical use, sustainable resource management, climate adaptation and protection against biological threats such as invasive species and pollution. Goal 1’s success accordingly depends on the other nine goals in the EIP.

This interdependence is crucial, but it also reflects a real implementation risk. Past failures and the complexity of environmental systems mean the success of Goal 1 cannot be taken for granted.

Commitments

Goal 1 sets out (and tabulates) a series of encouragingly concrete, measurable commitments and interim / statutory targets. Among these:

- Effective conservation and management of at least 30% of land and sea by 2030 (“30 by 30”).

- Restoration or creation of 250,000 hectares of wildlife-rich habitat outside protected sites by December 2030.

- Net increase in woodland and tree canopy cover by 0.33% of land area, equivalent to around 43,000 hectares (from a 2022 baseline).

- Support for farmland wildlife: doubling (by December 2030) the number of farms providing sufficient year-round resources for farm wildlife, compared with 2025.

- Reversal of species decline: statutory target to halt decline in species abundance by 2030.

- Restoration and management of hedgerows: support to create or restore 48,000 km of hedgerows by 2037 and up to 72,500 km by 2050.

Moreover, these commitments are backed by formal instruments: the interim and statutory targets under the Environment Act 2021, and a newly published Monitoring Plan that sets out theories of change, actions, outcomes and intended impacts.

On early analysis, Goal 1 appears to at least try to do more than set lofty ideals. It presents a legally and technically structured programme for nature recovery, against which the Government can be held to account.

Context

In the previous EIP (EIP 2023), Goal 1 was to achieve “thriving plants and wildlife”, and was explicitly treated as the “apex” goal for the EIP. EIP 2025 revises and widens that framing, presenting the restoration of nature as the ‘over-arching’ goal of the whole plan, but doesn’t reinvent the wheel.

The EIP update has – of course – not been published in a regulatory vacuum. There are currently more than 3,000 Defra regulations, alongside associated guidance, and the effectiveness of that regulatory landscape has been the subject of the independent Corry Review, published in April 2025. That review set out 29 recommendations, which included setting clearer outcomes for regulators and permitting greater flexibility and discretion to regulators to enable delivery.

The machinery of goal delivery is (at least in part) already under construction. However, reversing decades of habitat loss, fragmentation and species decline is a long game. Incremental legal protections and designations must be sustained and amplified to deliver real, landscape-scale recovery for this Goal to take effect.

Legal (and political) significance

My early-doors thoughts are that Goal 1 (which can’t meaningfully be read in isolation from the other Goals) offers cause for optimism as well as caution.

First, embedding these commitments in statutory targets, with accompanying delivery plans, monitoring and transparency, helps transform environmental ambition into accountability. EIP 2025 is not just a policy pamphlet: it appears to be a framework with teeth.

Second, by embedding restoration and conservation in national policy, EIP 2025 signals that environmental protection is central to future land use, agriculture, infrastructure, and development decisions. This may shift how courts and regulators approach environmental obligations, especially in habitat-related planning and licensing contexts.

Third, the scale of ambition (i.e. 30% by 2030, quarter-million hectares habitat restoration, doubling farm wildlife support) suggests a dramatic reorientation of the relationship between landowners, farmers, regulators, and nature. For many, this will represent a generational opportunity to reconcile production, development, and biodiversity. But it will also prove a test of political will.

Where scrutiny will matter

Goal 1, therefore, no doubt sets some bold ambitions. But, as is often the case, the proof will be in the pudding when it comes to implementation.

- Implementation complexity: “joined-up” does not guarantee joined-up delivery. The EIP’s interconnections are conceptually sound. But coordinating across dozens of sectors (transport, agriculture, water, waste, planning, energy), regulatory bodies and funding streams is notoriously difficult. Without genuine cross-departmental coordination and sustained political will, goals could be pursued in isolation, undermining the integrated approach the Plan depends on. Even on specific areas, implementation of good ideas can be a weak spot: the Office for Environmental Protection just last week (4 Dec) published a review of the implementation of laws covering Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protected Areas (SPAs), concluding that the main barriers to effectiveness involve implementation rather than the legislation itself.

- Balancing competing land-use pressures. Already, criticisms are being voiced by the NGO sector about the Starmer Government’s tension between narratives of growth and nature protection (see e.g. The Wildlife Trusts' response). With growing demand for housing, infrastructure, renewable energy, and food production, and with land and water constraints tightening, these competing prioritisation needs will inevitably arise. Although perhaps less intractable, there are also some inherent tensions between the Goals themselves, e.g. expanding public access to nature (Goal 10) could conflict with the ecological needs of fragile habitats unless strict controls are maintained.

- Timelines vs ecological reality. Habitat restoration must go beyond planting a few trees or designating a protected area. It must result in ecologically functional, biodiverse, connected landscapes. That requires long-term stewardship, funding for maintenance, and careful ecological planning. The EIP 2025 makes encouraging noises about working with stakeholders and communities, but we shall have to see how that works in practice. Many species and habitats take decades — not years — to recover. Soil regeneration, woodland ecosystems, wetland hydrology, species reintroduction and ecological networks evolve slowly. EIP 2025 sets many 2030 interim targets, but ecological recovery often unfolds on longer timescales. There is a risk that short-term metrics (e.g. hectares restored, woodland planted) will be used to signal success, while deeper ecological integrity remains poor.

- Monitoring and data gaps. EIP includes a new Environmental Indicator Framework (EIF) with many metrics for Goal 1 and other goals, ecological change (e.g. especially species abundance, ecosystem function, and habitat connectivity). But these metrics are hard to measure accurately at scale. For example, progress reports may focus on land-area or tree-counts, while missing declines in quality, species richness or ecosystem resilience. The new Monitoring Plan and indicator framework are promising. But we will be keeping an eye on how researchers, oversight bodies, in particular the OEP, and actors in the NGO sector respond as the EIP takes effect.

Natasha Jackson is a leading barrister at Landmark Chambers.

Must read

Sponsored articles

Walker Morris supports Tower Hamlets Council in first known Remediation Contribution Order application issued by local authority

Unlocking legal talent

Legal Director - Government and Public Sector

Principal Lawyer - Planning, Property & Contract

Senior Lawyer - Planning, Property & Contracts Team

Locums

Poll

20-01-2026 5:00 pm

12-02-2026 10:00 am

01-07-2026 11:00 am